From performance to business and scholarship, the love of music shapes lives and livelihoods.

When Jeremy Hecht was 17, he wrote a song hoping to save another teen’s life. Hecht had already been dabbling in posting his own music videos on YouTube and built a decent following. So, when a classmate shared a video link of a youth who was planning to take his own life, Hecht knew he had to do something.

“It was this kid recording himself saying ‘Goodbye,’” Hecht recalled. “I remember feeling so distraught and I decided to just turn on my mic to talk to him.”

Through the spoken-word piece, Hecht implores the boy to remember that “you are never alone, we are all in it together.” After posting his response to the “Goodbye” video, Hecht waited. A few hours later, the youth replied on the thread that he wasn’t going to “do it.” Hecht doesn’t know if what he said helped, but the episode did trigger his own epiphany.

“I turned the response into a song that night, called ‘Hold On’ and it was the most powerful thing I felt I had ever written. I remember thinking, this wasn’t my story, so, okay, maybe I’m the vessel to help tell other people’s stories rather than my own. And I loved that feeling,” said Hecht, who earned his master’s in strategic public relations in 2018.

Fed by this passion for a song, a beat, a lyric that was experienced early on, Hecht joins other USC Annenberg faculty, alumni and students who believe music has the power to unite us. Whether it’s composing the perfect phrase to convey how a song makes you feel or marketing a streaming service to the masses, they continue to explore the scholarly and professional dimensions of music and how it helps make meaning of the world around us.

“Our sense of who we are is always defined by somebody else’s life, by somebody else’s breath, by somebody else’s soul,” said Josh Kun, a professor and Chair in Cross-Cultural Communication. “It is the role of music to feed us.”

Somewhere over the rainbow

The Sunny Murray Band’s version of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” is playing as undergraduates pour into Kun’s “Sound Clash: Popular Music and American Culture” class. As they take in the syncopated rhythms of the jazz version, he asks them to think about how this rendition is different from the more familiar one sung by Judy Garland.

“I ask students to listen critically, to listen carefully, to focus, not just to have music on in the background,” said Kun, whose numerous books on the role of music in society include Songs in the Key of Los Angeles, and a forthcoming book on music and 21st-century migration. “Popular music is fun and entertaining, but laced within that pleasure and joy, and all of that emotion, and all of those tears and laughter, are meanings and definitions around race, ethnicity, identity.”

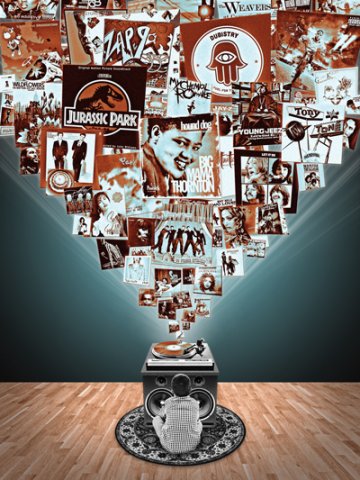

Kun traces his own deep connection to music to his childhood. He grew up listening to The Weavers and other folk groups who taught him music’s international role in social justice and protest.

“In my teaching, I ask students to think about what it means to connect through information, through emotion and affect and experience,” he said. “How music is one of those things that we all use every single day as a primary tool of connecting across the divides that surround us.”

Through this distinctive lens, Kun’s “Sound Clash” course created in 2005 provides a way for students to understand cultural and social change throughout the history of the United States.

Perry B. Johnson, who took the class as a sophomore, considers it a “culminating moment” in her academic career.

She also described a childhood rooted in song. As a high school student in Ojai, California, she sang a cappella, even performing in Carnegie Hall with her classmates. But she didn’t see a career path for herself as an entertainer.

After taking Kun’s course, she realized that music didn’t have to be a hobby. “I could explore music as an entry point to think about America’s complex cultural histories, to think about identity, about power, about belonging,” she said.

With her academic trajectory pointed toward the study of music as communication, Johnson remained at USC Annenberg, earning a bachelor’s in communication in 2010 and a master’s in communication management in 2011. In 2014, she enrolled in the communication doctoral program.

Johnson’s journey came full circle in 2018, when she was offered the opportunity to teach Kun’s “Sound Clash” course herself. In one lesson, she urged students to look at songs as a way to explore race, power and visibility within the American music industry. She pointed to Elvis Presley’s 1956 rendition of “Hound Dog” as an example, tracing the track’s history back to Big Mama Thornton, the Black woman who originally recorded the song in 1952 and was largely erased from history in the wake of Presley’s hit.

After earning her PhD this past summer, Johnson joined the Center for Media at Risk and the Annenberg Center for Collaborative Communication at the University of Pennsylvania as a postdoctoral fellow. The center is a collaboration between USC Annenberg and Penn’s Annenberg School for Communication. This Fall, Johnson is teaching a class there, modeled after “Sound Clash.” She is also at work on the manuscript for her first book, a cultural history of sexual misconduct in America’s popular music industries.

“I’m still very interested in exploring what music means in terms of who’s visible in particular moments and how that then becomes the history of American music more broadly,” she said.

Waiting on the world to change

From his earliest childhood memory, Aram Sinnreich was “obsessed” with music. He recalls sitting on the floor, listening to his parents’ records — Beatles, Everly Brothers, Rolling Stones — and learning every “lick and every lyric.” During theater camp at age 12, he was taught a few chords on the guitar, and after that he never put it down.

While Sinnreich continued to write songs and play in a band, Dubistry, throughout his career, it was a job working for Jupiter Research in the late ’90s that pushed him toward academia.

“I was working as an internet industry analyst and my job was to write reports about how the web was going to change various industries, specifically media,” Sinnreich said. He recalls talking to his boss, suggesting they look carefully at how music would be transformed by technology. They patted him on the head and told him his predictions were “cute.”

Then Napster hit, and Sinnreich couldn’t understand why the music industry didn’t embrace streaming as a way to double in size. Finding that “intellectually confusing,” he chose to pursue a doctorate in communication at USC Annenberg to find answers.

What he dug into was the idea of authorship. Even though a song is a discrete object, Sinnreich wanted to investigate what it means when a DJ “tears the song apart,” adds it to another song — essentially creating a mashup of the two songs. Does that DJ then become an author in their own right?

Earning his doctorate in 2007, Sinnreich is now a professor and chair of communication at American University. He views music not as a commodity, but rather “the operating system of human consciousness and human society.” By lowering the barriers of access to music and giving people opportunities to explore it in different ways, individuals become more expansive in their thinking.

“It’s not that the internet changed us, but it’s that the internet allowed us to be more authentic to ourselves in terms of how we listen and how we make sense of the world through music,” he said.

Alile Suh, head of global public relations at the French online music streaming company Deezer, also views streaming as a game changer for music discovery.

“There’s this genre-bending that’s happening within streaming services,” she said. “For example, Deezer has a playlist called ‘ANTI,’ for those that actually don’t care about a specific genre. Artists now have an opportunity to reach different audiences that normally might not think they like their type of music.”

Recalling her own teenage years, Suh, who earned a master of arts in journalism in 2004, remembers going into record stores to search for indie, alternative rock or hip-hop CDs. Nowadays she believes people are much less pigeonholed in their music tastes. “Growing up, I was so used to listening to certain types of music based on what I was familiar with, but now with streaming, I can dip my toes in everything from Grime to Japanese LoFi hip-hop,” she said. “There’s definitely more opportunity for me to quickly discover music from around the world.”

Suh, who works in Deezer’s Berlin office, points out that this new technology gives audiences extraordinary access to global music. In the PR campaigns she oversees, she encourages users to find new music in order to learn about something beyond themselves. “We also use music to raise awareness,” Suh said. Following the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, Deezer launched a dedicated Black culture channel highlighting Black artists and creators across multiple genres such as pop, classical and dance. For International Women’s Day, they celebrated by featuring only female artists on the platform. “Streaming is so different from that record store, because there’s a never-ending supply of pretty much everything you can find to educate yourself.”

Applause

“I was just a kid who loved music and I carried my Walkman and fuzzy purple CD case everywhere,” she said. “All my money and free time went to flipping through albums at Best Buy, going to concerts and making mix CDs for my friends. When they got the cassette tapes they weren’t even, ‘What song is this?’ They would ask, ‘What artist is this?’ I always very much wanted to keep my finger on the pulse.”

Moran, now the director of tour development at Warner Music Nashville, originally dreamed of going to the Juilliard School and becoming a singer. When she hit high school and recognized that she didn’t sing as well as some of her peers, she switched plans. “I still knew that I had to be involved in music in some way,” she said. This passion drew her from Virginia to Los Angeles, where she majored in public relations at USC Annenberg and minored in music industry at the USC Thornton School of Music, graduating in 2013.

While at USC, Moran learned how to create strategic PR campaigns, to think critically and to network — skills that were easily transferrable to her career. In fact, she got her start at Warner Records (formerly Warner Bros.) through an internship opportunity with a USC Annenberg alumnus.

A year after graduation, Moran returned to Warner Records as a promotion assistant before moving up to her current position in Nashville. Moran is now responsible for adding value to all live events — whether that’s helping a developing act land a support slot, setting up a livestream or building a unique promotion to get fans excited about a tour.

“I love how my job constantly reminds me of the spiritual, emotional and precious bond between fans and artists,” she said. “There’s nothing like standing with fans in the pit and feeling that energy.”

Roderick Scott, the alumnus who gave Moran her shot, graduated in 2007 with a bachelor’s degree in communication and a minor in advertising. He was born in Arizona to a military family who moved to Portugal when he was a young child and later landed in Sacramento. His mother sang in the church choir, and his father created mixtapes filled with R&B, gospel and funk, with artists like Roger and Zapp and Tony! Toni! Toné!

At USC Annenberg, Scott said he acquired the tools needed to “persuade, to coerce, to get an audience to tap into whatever you are building.”

Beginning his career at Warner Bros. in media relations, Scott was one of the first people in publicity to really embrace the digital space, citing the ability to get instant metrics on a campaign as a key to his success. “The digital space offered us the opportunity to see real metrics and quantitative data on what we’re trying to promote,” he said.

Scott moved on to Atlanta Records in 2017 before being asked to join Republic Records in 2020. Now the vice president of marketing strategy at Republic, Scott’s role is to help steward artists’ dreams.

“My job starts when the music is already delivered, and the musician comes to us to help figure out what to do with it,” Scott said. He explains that helping artists cut through the noise and create an emotional connection with consumers — with fans — is the most crucial part of his job, asking them to think about why their voice matters at this particular time.

Story of my life

In a dual content creation role as a music journalist and digital content producer at HipHopDX, a subsidiary of Warner Music Group, Jeremy Hecht understands that when creating content about musicians, it’s his job to dig deeper and find the meaning behind their words.

Hecht illustrates by sharing an opportunity he had to interview American rapper Jeezy. Another reporter had been set to do the interview but wasn’t available at the last minute. Jeezy was already at their offices and Hecht, who had come up with all the questions, convinced his boss to give him a shot. “I promise, I got this,” Hecht said. “One of my questions was literally me as a fan, wanting to know something that apparently hundreds of thousands of other people wanted to know: ‘How did your ad-libs end up on Kanye’s “Can’t Tell Me Nothing” song?’ And the story behind it was so crazy it went viral.”

Hecht said his true joy comes from telling an artist’s story in a way that might “inspire someone to be their best self.” This same drive to contribute to someone else’s musical journey also motivated Tim Greiving.

Even as a kid, Greiving loved to interview people and would go around his neighborhood, cassette recorder in hand, to find stories and then write them up. “I was unwittingly kind of doing journalism at the time,” he said.

His music origin story began when he turned 9 and heard the Jurassic Park film score for the first time. “My older cousin was already into film scores, and he explained the whole concept of composers who write original music for movies,” Greiving said. “I went home — back to Denver — bought the music, and that began my obsession with John Williams specifically, and film music generally.”

With a combined love of music and journalism (and no desire to pursue a career as a composer), Greiving found the master of specialized journalism (the arts) program to be the perfect fit for him. Since graduating in 2012, he has written for the Los Angeles Times, NPR, Washington Post, New York Times and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and considers himself more of an evangelist for music, rather than a critic.

“It’s a fun challenge to try to write about music in a way that, if you’re just reading the words, you can convey what the music sounds like, or how it makes you feel — without it being boring and technical,” he said. “My goal is to whet the appetite of a reader, and also, maybe, make them want to run out and actually listen to the music.”

Greiving, who is also an adjunct professor at USC Thornton, shares this appreciation with his current crop of students, describing his course as less about musicology and more about “spreading my love of film music.”

Talking about my generation

As the next generation of students prepare for careers in music, USC Annenberg continues to add both curricular and co-curricular opportunities for them. Along with Kun’s transformative “Sound Clash” course, students can take classes such as “Youth and Media,” “Image Management in Entertainment” and “Public Radio Reporting,” — all with units focusing on music. The school has also added experiential learning options outside the classroom.

This year, USC Annenberg Board of Councilors member Manuel Abud, CEO of The Latin Recording Academy, approached the school’s development office with an idea. He wanted to bring current students, ideally bilingual in English and Spanish, to the Latin Grammy office to help create a multiplatform digital campaign. The plan was for students to work with his team to help inform and demystify the judging process for their audience. “Working with these emerging leaders in communication to facilitate research enables us to evolve in a meaningful way, providing a fresh lens on storytelling that meets audiences’ needs while delivering on our mission to nurture, celebrate, honor and elevate Latin music and its creators,” he said.

Emanuel Rodriguez was the type of student they were looking for. His own love of music stemmed from car rides with his family through the streets of Kansas City, Missouri. Rodriguez, a junior majoring in communication, remembers either pop songs playing on the radio (Lady Gaga was a favorite), or his sister’s MP3 player blasting out reggaeton.

It was this broad interest in the entertainment industry that initially prompted Rodriguez to enroll in the communication program, taking courses in “Global Entertainment” and “Communication and Mass Media” and later writing music reviews for the Daily Trojan.

Then, this past Spring, Rodriguez and four other USC Annenberg students were chosen by the Academy as interns. Since March, they have been working on messaging, creating quizzes and video content for the Latin Grammy website and social media channels. Rodriguez described editing video interviews of artists, such as Gloria Estefan, and producing informational campaigns about academy roles and processes for TikTok and Instagram, as an amazing opportunity.

“A big part of the Annenberg education is to expose you to different perspectives and then learn how to communicate from those perspectives,” he said. “This whole experience — both my classes and this internship — gave me the chance to really think about why this sort of music and why these different viewpoints are important, and it made me even more appreciative of my own culture.”