Demands on companies and their CEOs to take stands on social issues ranging from immigration to climate change, gun rights to gay rights, Brexit to global trade, have rapidly accelerated in the past two years.

Additionally, companies are now being urged by many investors to demonstrate positive social impact. In his widely reported letter to CEOs this past January, BlackRock’s Larry Fink wrote, “Society is demanding that companies, both public and private, serve a social purpose. To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society.”

The pressure on CEOs to take stands on social issues comes from customers, employees, even the president — just ask the NFL. When deciding whether to engage, companies must weigh risks and benefits that are often difficult to identify and even more difficult to quantify.

To thread this needle successfully, companies must have a more structured, thoughtful, and effective approach to all forms of social engagement. Professor Paul Argenti of Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business, suggests there are four key questions to ask:

Strategic values alignment: How relevant is this issue to our core business and values?

- Risk: How controversial is this issue? How might our firm gain? What might we lose?

- How: Can we take action, tie our motivations to our business or share our beliefs?

- Urgency: How urgent is it that my firm respond?

For purposes of this discussion, we can assume that the risk is relatively high — that we are dealing with a controversial issue on which there is likely to be disagreement among our customers and our employees, and that it may invite attention — both wanted and unwanted from the outside.

Urgency is likely to be closely related to how closely the company is already associated with the issue, particularly if the company is under attack in a crisis. The NFL, for example, could not avoid dealing in some way with its players’ anthem protests because of the level of public interest in the subject and the dispute with Colin Kaepernick over whether he’d been effectively banished from the league in retaliation.

President Trump only upped the ante further. But Nike’s dramatic engagement in the issue, making Colin Kaepernick the face of the brand in its “Believe in Something” campaign, was purely voluntary, the result of a calculation that it has more to gain than to lose — a calculation that initial sales reports indicate was correct.

Starbucks faced an issue it had no choice but to engage on when in April two African American men waiting for a friend in a Philadelphia Starbucks were wrongly arrested for trespassing after the manager called police. The issue exploded across the country, seen as an example of how African Americans are harassed or even arrested for engaging in ordinary activities. Starbucks responded by apologizing to the men, and then closing more than 8,000 stores for staff training, adopting a new policy that broadly defined “customer.” It also re-committed itself to be a “third place” between home and work, albeit with a customer code of conduct that includes “using spaces as intended” and guidance for employees on when it is appropriate to call 911.

Sometimes, a company may need to engage on an issue that becomes magnified by a much larger public policy debate. The controversy that erupted this year when Cambridge Analytica was found to have collected personally identifiable information of more than 87 million Facebook users, and then used the information to influence voters, became inextricably linked to the larger debate over data privacy, manipulation of content, fake news and Russian interference in the 2016 election.

In yet other instances, a company may engage on an issue not out of crisis but because it is related to the brand. Patagonia, the maker of high-end outerwear, prominently criticized the administration’s order to shrink two national monuments in Utah, and although the move was well-received by many of its customers, it also generated a boycott effort.

The hardest questions involve whether and how to engage in hot-button issues that are neither forced upon the company through crisis nor are closely related to the brand. They are social issues on which the company wants to — or is being pressed to — become involved. In September, Levi Strauss pledged more than $1 million to support nonprofits and youth activists working to end gun violence. The company’s CEO acknowledged that “we’re going to alienate some consumers” but said he was convinced it was necessary to do more in the aftermath of the Parkland, Florida school shooting.

And while an invitation to the White House can be hard to turn down, involvement in presidential task forces carries risks. After the CEO of the DC-area’s Taylor Gourmet sandwich shops announced he was joining a White House roundtable on small business, sales reportedly dropped 40 percent and never recovered. In September, what had only recently been a growing chain suddenly announced it was shuttering all 17 stores and said to be headed for bankruptcy. Earlier, GE’s former CEO Jeff Immelt took considerable heat from some customers and shareholders for leading President Obama’s jobs council.

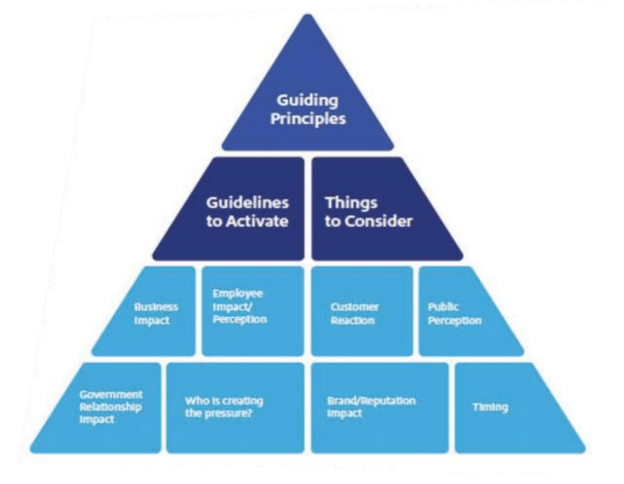

The lesson is that before voluntarily engaging on controversial issues, some form of structured decision-making is essential. Southwest Airlines has adopted this pyramid:

The questions Southwest asks include (but aren’t limited to):

- Which employees are affected? How? Will it affect our status as a “Best Place to Work”?

- What is the cost to our involvement? Does it outweigh the gain?

- Which shareholders and board members are affected? How?

- What customers will we alienate by both the decisions to engage and not to engage? Will we lose them?

- Does what we’re saying match what we’re doing?

The last two questions deserve particular attention. Professor Argenti urges companies to consider the opportunity cost of not responding, and notes that fully half of millennials want the CEOs they work for to speak out on the issues they care about. On the other hand, an owner’s high-profile stance on controversial issues can complicate a company’s reputation even when the company itself doesn’t engage.

Finally, the decision of whether to engage and how to calibrate the effort isn’t just made once for a given issue. It must be re-evaluated and fine-tuned frequently in light of changing circumstances, in crisis situations possibly even more than once a day. For that reason, an effective program to monitor and analyze the surrounding conversation — mass media, social media, input from customers, and more — is absolutely essential to empirical and effective decision-making. And while technology is important, companies shouldn’t overlook the human factor: an outside advisory board, one that is more than window dressing and can be turned to for honest feedback and insight, has proved valuable for many different kinds of companies.

To download a full copy of the 2019 Relevance Report, click here.