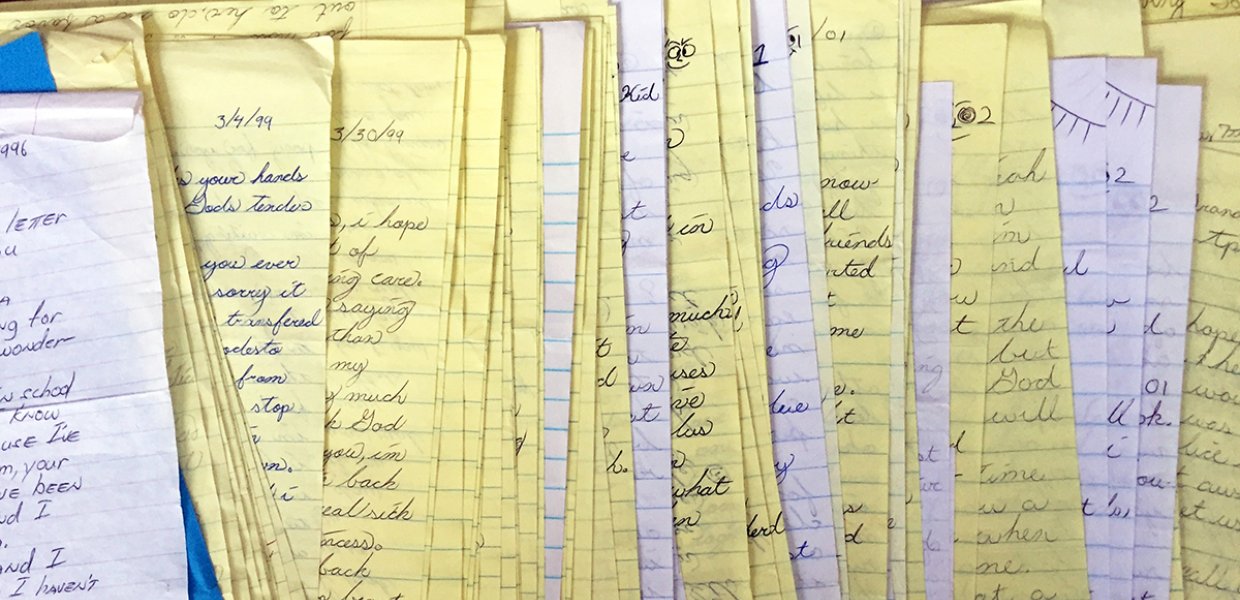

For Melissa Dueñas, Father’s Day is a particularly poignant holiday. From the time she was two and a half years old until she turned 20, her father was in and out of prison. From her childhood through her teen years, Dueñas wrote him letters, sometimes weekly, sometimes monthly, later only a few times a year, until he died in 2017.

Over the last few years Dueñas, who will be graduating with a master’s degree in specialized journalism (the arts) from USC Annenberg in August, has been looking for ways to share these letters with a broader audience and create visibility for untold stories.

It wasn’t until she took a public radio documentary class in her graduate program at USC Annenberg that she found the perfect medium.

Sandy Tolan, professor of journalism, and Ruxandra Guidi, a health journalism fellow, who taught the class, shared with students the opportunity to present their project to KQED’s “The California Report,” a public radio station that covers news and culture from California. As the graduate students brainstormed ideas to pitch to the executives, a few suggested writing about people who had been incarcerated.

At this point, Dueñas shared her story — and the letters — with the class.

“If we are going to do this,” Dueñas suggested, “We are going to need other voices, including families. I think the family is really left out of these stories, and how it's affected them is important.”

Both her peers and professors urged her use the archived letters to produce a project that experimented with the audio form. “It was emotional,” Dueñas said. “I won’t deny that — doing personal pieces, especially about traumas, is no light undertaking.”

Using voice actors reading each of their parts, Dueñas produced a 14-minute audio documentary that airs on Friday, June 14, two days before Father’s Day. The piece incorporates music cues that were designed to introduce themes in the story. Dueñas said music has always been an integral part of her life, whether she is collecting records, DJing or playing the drums.

In this intimate memoir piece, “Dear Dad: Letters to my Incarcerated Father,” Dueñas explores their complex relationship. Growing up, “I felt very close to my dad — I could tell him anything,” she said. “From my childhood, there was a letter where I told him, ‘I feel like you're the only one who understands me.’”

Her personal letters have a stream-of-consciousness feel. She would fill her dad in with the day-to-day — her personal life, school life, family life, whether it be a basketball game she won or the family car breaking down. She would then sign off with, “Okay, love you, bye.”

When she hit her teen years, things changed as her anger and resentment surfaced. “I’m telling him, ‘You’re the only person that understands me’ one year, and the next, ‘I don’t even know you,’” she said.

Dueñas learned early on how to see the duality in people. “It was really important for me to capture the enfolding, contradicting emotions in the story,” she said. “I don’t think we talk about that enough — loving people who have done bad things. It’s this combination of knowing my dad is not a good person, but still loving him and knowing that he was a good person in some other ways,” she said.

The process of working on this project was both challenging and healing, she said. Tolan and Guidi offered support, helping her navigate how to be both a producer and a participant on a project. “I wanted to make sure my family’s voice was heard. That was probably the hardest part for me, editing and making sure I was doing them all justice. I didn’t want to make them sound one-dimensional,” she said.

This process also taught Dueñas a great deal about journalistic ethics and the relationship between reporter and subject. “Journalists are not therapists, but if we’re going to be asking people to share things that are traumatic, we need to be careful and we need to always keep their emotional wellbeing at hand,” she said.

As far as its Father’s Day release, Dueñas wanted to offer an alternative narrative to the greeting card-type Father’s Day experience. “Holidays are triggering for a lot of people, and there’s this shiny Father’s Day that we project on people, but there are those who don’t know their dad, or have troubled, complicated relationships with their father.

“Of course, this story is unique to me, but the experience of loving someone who is incarcerated is unfortunately common,” she added. “I want people to be willing to share their story. There is plenty of room — it’s a good time to be a storyteller.”

To listen to Melissa’s audio documentary, click here.