Conversation is important to Professor Henry Jenkins.

He’s written and/or edited 17 books over the last twenty-five years, he’s a prolific blogger at Confessions of an Aca-Fan, he teaches at both USC Annenberg and the USC School of Cinematic Arts, and in all of those roles, he focuses on the interplay between audiences and art and on participatory culture.

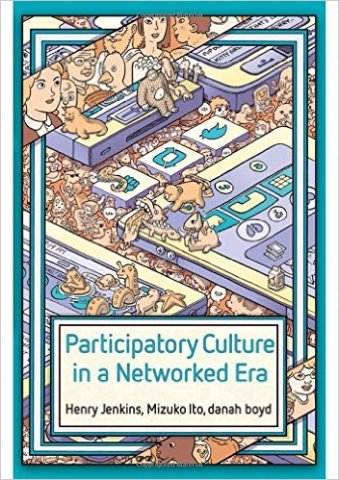

Jenkins’s most recent book, “Participatory Culture in a Networked Era” (Polity 2015), is a conversation about conversation. In it, he and two long-time collaborators, danah boyd and Mimi Ito, look back over the past few decades to see what has and hasn’t changed in their research on participatory culture.

In structuring the book as a conversation, Jenkins and his colleagues give a behind the scenes look at “how scholarship happens,” as his co-author, danah boyd, put it in a recent post on Jenkins’s blog.

“I have been experimenting for some time,” Jenkins said, “through my blog and my academic publications, in how we can foster interdisciplinary conversations between scholars about the points of convergence and disagreement in their work. ‘Participatory Culture’ is perhaps my most ambitious project along this line.”

Jenkins said that his work has always been in dialogue with that of his co-authors but “at the same time, we come from different disciplinary backgrounds, we travel through somewhat different circles professionally, and we work on different communities of youth.”

danah boyd, who is a Principal Researcher at Microsoft Research, the founder of Data & Society, and a Visiting Professor at NYU, works on youth and social networking platforms. Mimi Ito, a Professor in Residence and MacArthur Foundation chair in Digital Media and Learning at University of California, Irvine, researches digital youth and connected learning.

When Jenkins was approached by his publisher to do a book-length interview on his career, he proposed, instead, that the book be a conversation between himself, boyd, and Ito.

In writing it, the trio reflected on what they had and hadn’t anticipated about the rise of new media.

“In some ways,” Jenkins said, “the digital is not as transformative as we sometimes imagined: neither as good nor as bad as earlier writers predicted. In some ways, we are just now confronting issues of inequality in access and participation that are going to have profound consequences over the next few decades.”

All three co-authors tend toward optimism, said Jenkins. So when they first began their research into participatory culture, they were “often accused of being too celebratory” when writing and talking about online communities in which each participated themselves.

But through their work of the past ten or fifteen years, Jenkins explained, “We became more and more concerned with who was being left out of the cultural practices we were documenting through our research.” Not everyone, they found, is able to or welcomed to participate.

“Throughout,” said Jenkins, “we keep circling around what happens when these ‘virtual communities’ (to use a classic formulation) encounter people from different backgrounds, when their commitments to diversity get tested.”

They also explore the issue of access to technology, as well as access to opportunities involving technology. Children and teens are often assumed to be fluent with new technology and social media, but in that assumption, a large number of youths are ignored.

Jenkins said that he and his co-authors “try to dislodge some of the myths that get encoded into the language we use to talk about youth’s networked lives.”

“The phrase ‘digital native’ masks the various kinds of inequalities in terms of youth access and participation, inviting us to imagine a world where all youth are naturally skilled at new media practices by virtue of having come of age in a world with networked computers in it.”

While many young people are, indeed, frequent and proficient users of technology in a world that is becoming more and more participatory, according to Jenkins, “many are still struggling to be heard.” It’s an issue he calls “urgent to address.”

Jenkins and his co-authors hope that their book will be a valuable look into how scholarship is produced and will encourage more people to join the conversation.

Writing on his blog, Jenkins said, “We need more of this kind of academic dialogue—not reading papers to each other at high speeds at conferences, not throwing out messages in bottles (or journals, which can take even longer to reach their recipients), but in sitting down in real time, sharing thoughts, responding thoughtfully to others, and challenging established wisdom.”

Read more discussion between Henry Jenkins, danah boyd, and Mimi Ito at Confessions of an Aca-Fan.