The following article by MS in journalism student Bulbul Rajagopal and professor of professional practice Gabriel Kahn originally appeared on Crosstown, a joint data-journalism project of USC Annenberg and the Integrated Media Systems Center at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering. Directed by Kahn, a USC Annenberg professor of professional practice, the Crosstown team was able to quantify recent data on how confirmed cases of COVID-19 show some alarmingly high rates in some of Los Angeles’s richest enclaves.

“One dynamic of this health crisis we need to understand is, where are the densest clusters?” Kahn said. “The way to do that is to compare the confirmed cases against population. Looked at through this lens, Long Beach may have more than 100 cases, but its infection rate is quite low. The Fairfax neighborhood in L.A., on the other hand, has fewer cases but the highest rate in the county.”

The most recent data on confirmed cases of COVID-19 show some alarmingly high rates in some of Los Angeles’s richest enclaves: Bel-Air, Beverly Crest and the Hollywood Hills all have infection rates over 100 per 100,000 residents, as of April 1. Hancock Park‘s rate is over 200. Middle and lower income areas such as Huntington Park, South Park and Boyle Heights, meanwhile, all had rates under 25 per 100,000.

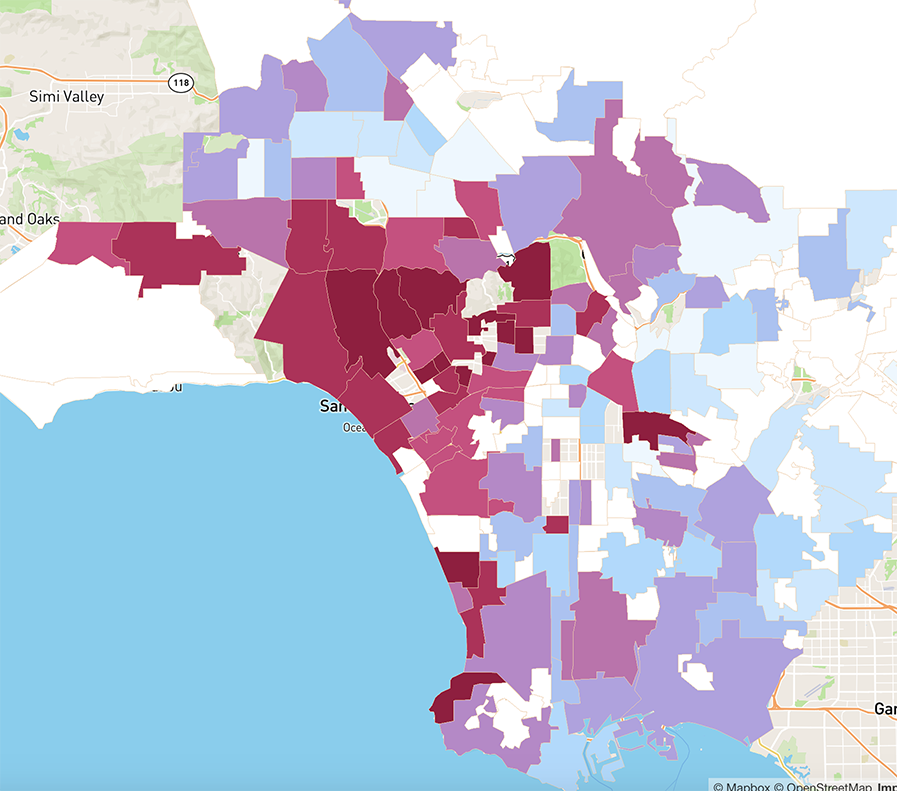

[See our map of where cases are concentrated in Los Angeles County]

The numbers raise a question that is as much about wealth disparity as it is about health: Does the data show who is infected or who can afford to get tested?

Clusters of wealth, clusters of cases

Crosstown compared data on the location of confirmed coronavirus cases released by the Los Angeles County Department of Health against population in order to see which areas have the highest rates of infection per 100,000 residents. We built a map to display our findings: Many wealthy parts of the county have some of the highest rates. Brentwood and Palos Verdes Estates, for example, both had a rate above 100.

To be sure, there are also many middle- and lower-income areas that are suffering as well. Neighborhoods such as West Adams and Valley Village, for example, have high rates above 50 per 100,000, but do not have the super-high incomes of Bel-Air. The densest cluster of cases in the county is the upper-middle-class Fairfax district, at 724 per 100,000 as of April 1.

The high infection rates in certain wealthy areas offers another piece of evidence to a debate that has raged around how the nation’s health system responded to the outbreak.

“One thing we do know is that there is a lot of selection with who is and isn’t tested, which are driving the numbers we see now,” said Robynn Cox, a professor of social work at the University of Southern California and a fellow at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics. “The larger numbers in affluent communities may be a result of the ability to pay a higher price to obtain testing.”

Who gets tested

Concern about whether access to testing was skewed toward the wealthy first emerged several weeks ago, when a number of athletes and celebrities revealed they were infected. On March 17, the Brooklyn Nets announced that four players had tested positive at a moment when New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo was decrying a critical shortage of tests in the state. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio responded to the news on Twitter, writing, “Tests should not be for the wealthy, but for the sick.”

On March 19, the Los Angeles Lakers announced that two of their players also had the virus.

The Medical Board of California has opened a review of so-called “concierge” doctors around L.A. who were offering their well-to-do clients access to the test at exorbitant prices, the Los Angeles Times reported.

California, in particular, has suffered from a severe shortage of tests. As of March 27, New York had tested three times as many people as California, the Associated Press reported, though its population is half the size as the Golden State’s.

On March 30, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced that, so far, the city had tested 6,741 people for the virus, but he hoped to double that number in four days.

Rationing the kits

As more testing becomes available, some of the initial results, which tilted toward higher rates in wealthier areas, might also flatten out. For the moment, however, the health authorities in Los Angeles have placed strict criteria on who should be tested, rationing the kits first to those who are 65 or older, are showing flu-like symptoms and have been exposed to another person who is confirmed to have COVID-19.

Katherine Tangalakis-Lippert, a graduate student of journalism at USC who lives in Simi Valley, first showed symptoms of COVID-19 on March 17. By that point, Tangalakis-Lippert, who has asthma, had a chronic cough and was short of breath. She eventually visited an emergency room on March 29. After she tested negative for strep and pneumonia, doctors swabbed her for COVID-19. Her test results will take a week, however, as a backlog in the state has led to excruciatingly long wait times. In the meantime, she is recuperating at home.

“I honestly don’t know what normal is in this pandemic,” Tangalakis-Lippert said. “In this case, I don’t think it’s good that the waiting period is a week.”

According to Vox’s report of testing by state, 90,657 people had been tested for COVID-19 in California as of March 30. The Los Angeles County of Department of Public Health informed Crosstown that as of March 29, over 15,500 people have been tested in the county alone.

You can read the original article here.