Calls about loud parties, fireworks, road hazards, take up a lot of LAPD time.

What do the roughly 10,000 officers of the Los Angeles Police Department actually do?

The Los Angeles City Council is now considering some sweeping changes to the way LAPD officers operate, potentially pulling them away from responding to many non-emergency situations and replacing police officers with social service workers, mental health professionals and other experts. The council’s proposal is an attempt to respond to the growing calls to defund the police and reduce its $1.8 billion budget.

Crosstown analyzed the nearly two million records detailing what kind of calls police responded to last year and what actions they took while on patrol. The data includes everything from 911 calls to traffic stops. Advocates for reform note that in recent years police have been tasked with a growing number of responsibilities, many of which have nothing to do with criminal activity. This has led to an expansion of officers’ roles and the department budgets.

Loud parties, fireworks and lunch

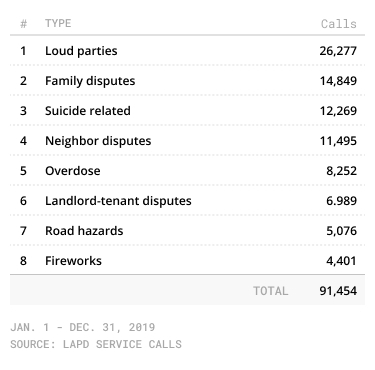

Indeed, many of the calls police received in 2019 appear to have had little to do with fighting crime. For example, loud parties drew the police out 26,277 times last year, according to LAPD’s service call records. Officers responded to 4,401 calls about fireworks and 3,109 complaints about early morning construction noise. There were 3,514 instances in which the police were called because of disputes among roommates. On 909 occasions officers were dispatched to check out potentially unauthorized auto repair garages.

Also among the two million service call records: 128,224 instances of “Code 7,” when officers took official meal breaks.

There are plenty of crime-related calls that keep officers busy. Last year, police responded to 51,226 calls related to trespassing and 47,808 calls for burglary. And one of the most common categories of calls police received related to domestic violence. In 2019, the LAPD received 41,193 of them.

The LAPD notes that studies have shown the best protection for a survivor of domestic abuse is court intervention. The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence said on their website if someone is in immediate danger they should call 911.

But there are other categories of calls, such as responding to calls about potential suicide, for which police might not be the best equipped to address. There were 12,269 calls related to potential suicides in 2019. Indeed, even some California law enforcement agencies have tried to pull back from addressing suicide-related calls.

Top non-criminal call types received by LAPD in 2019

According to the data, what occupies officers most are not calls from the public, but issues they notice while in the field. There were 898,622 instances of “Code 6,” which is when officers on patrol respond to something they see taking place on the street or are flagged down by someone.

Another focus of police time: traffic stops. Last year, officers pulled over vehicles 128,224 times. The LAPD has come under scrutiny for using vehicle stops as a pretext for conducting a disproportionately high number of searches of Black and Latino drivers.

Reform advocates and lawmakers are now examining how much money could be cut from the LAPD budget and reinvested elsewhere if the police were exclusively dispatched to respond to criminal or dangerous situations. Mayor Eric Garcetti has pledged to reinvest $150 million of the police budget into other areas.

“Overwhelmingly, the call was that we wanted to invest in universal needs and divest in traditional forms of policing,” David Turner, a researcher for Black Lives Matter LA, said during a presentation Monday of the People’s Budget. The People’s Budget is a set of city spending priorities proposed by a coalition of community organizers, nonprofits and individuals across Los Angeles.

“What would it look like, if instead of law enforcement shooting people with rubber bullets and tanks, we use some of that money and we used it to invest in protective equipment for our city workers?” Turner said. “What would it look like if we had that type of infrastructure in place?”

Redefining the LAPD’s job

Councilmember Herb J. Wesson, Jr., who attended the presentation, responded on Twitter, writing, “We have gone from asking the police to be part of the solution, to being the only solution for problems they should not be called on to solve in the first place. … These calls need to be directed to workers with specialized training who are better equipped to handle the situation.”

The May 25 killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police has sparked nationwide protests against police brutality and systemic racism.

In a recent essay in The Wall Street Journal, Barry Friedman, director of the Policing Project at the New York University School of Law, said that policing strategies of the past 40 years stem from policymakers deciding that an armed person should address society’s biggest problems.

“The problem, simply put, is this: We send police officers to deal with too many social problems — substance abuse, mental illness, homelessness, domestic disputes, even civil unrest — for which they are grossly unprepared,” he wrote.

Last week, San Francisco Mayor London Breed announced her plans to address structural inequities by changing how policing works in her city. Breed’s proposal includes ending the use of police to respond to non-criminal activity, addressing police officers’ implicit biases and demilitarizing the police.

“San Francisco has made progress reforming our police department, but we know that we still have significant work to do,” she said in a statement. “We know that a lack of equity in our society overall leads to a lot of the problems that police are being asked to solve. We are going to keep pushing for additional reforms and continue to find ways to reinvest in communities that have historically been underserved and harmed by systemic racism.”

The Los Angeles Police Protective League, the main police union in the city, has pushed back against calls to reduce the force’s budget. But Tom Saggau, a union spokesperson, said they are open to reevaluating the calls the LAPD responds to. He said that policymakers, not police, were the ones who have decided how the police are deployed.

Saggau said the police are already not meeting their quotas for responding to 911 calls quickly enough and agreed policymakers should look at investing in mental health services. But he had reservations about the safety of social workers responding to volatile situations involving domestic disputes and people experiencing homelessness who may also be suffering from mental health issues.

“There are unintended consequences that need to be well thought out,” said Saggau. “The last thing we want to do is respond to a call where the social worker needs help from the LAPD. There are certainly models that work, but it takes investment.”

The People’s Budget asked for those investments by calling for nearly 71% of the city’s budget to go toward the public good, crisis management and “reimagined” public safety.

“We want a better Los Angeles and a better world,” said Melina Abdullah, co-founder of Black Lives Matter LA at a City Council meeting on Monday. “This is a moment where the world has cracked open and you all have the opportunity to really be courageous and do something different in the City of LA.”

She added, “Imagine what can be.”

This piece was originally published on Crosstown.

How they did it: They examined LAPD service call data from Jan. 1, 2019–Dec. 31, 2019.

Interested in the data or have additional questions? Email askus@xtown.la.