This story was originally published on Crosstown and is republished here with permission.

Last year, 1,383 people experiencing homelessness died in Los Angeles County.

On the first day of 2020, the unresponsive body of Corinna Ortega, a Latina woman, was discovered by a friend in a tent in Parnell Park in Whittier. The coroner would rule that Corinna, 22, died of a fentanyl and methamphetamine overdose.

That same day, Sean Austin, a 46-year-old white man, was found dead at 4 a.m. beneath an overpass in Wilmington. He died of an overdose, this time due to methamphetamine and alcohol.

Larry Roberts, a 64-year-old Black man, was also discovered that day, in a car at the intersection of Century Boulevard and Zamora Avenue in Florence-Firestone. Larry died of heart disease.

All three individuals were experiencing homelessness at the time they died, and while each passing was tragic, the Jan. 1 deaths were no outliers, and turned out to be somber predictors of the year to come: A total of 1,383 homeless individuals died in Los Angeles County in 2020, said Sarah Ardalani, a spokesperson for the Los Angeles County Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner. She noted that the totals are preliminary.

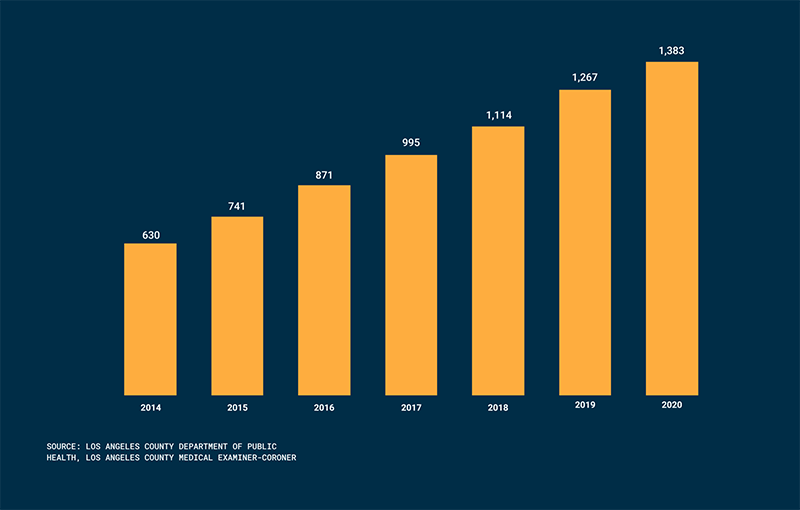

The figure marks a grim record for Los Angeles, surpassing the 1,267 homeless individuals who died in 2019. The 2020 total also works out to nearly four people experiencing homelessness dying each day.

The coronavirus pandemic is not solely to blame, as the number of deaths has risen steadily for years. The 2020 figure is a 104 percent increase over the 630 people experiencing homelessness who died in 2014, according to data from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Deaths of people experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County

Data from the Medical Examiner-Coroner provides insight into the epidemic of deaths of people experiencing homelessness. The increasing number corresponds with a rising homeless population. The 2020 Homeless Count, conducted by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, found that there were 66,436 people experiencing homelessness in the county, a 12.7 percent rise from the previous year’s point-in-time count. The city of Los Angeles recorded a 16.1 percent increase, to 41,290.

The federal government reports 1.5 million people a year experience homelessness. Other estimates say the figure could be twice as high, according to the National Health Care for the Homeless Council.

The Los Angeles count took place before the coronavirus pandemic began. The 2021 count, scheduled for January, was canceled due to the threat of COVID-19, though many experts believe homelessness is rapidly increasing because some people’s incomes have been evaporating due to the economic crisis.

Data detailing where and how people died, as well as personal information about the deceased, reflects the complexity of homelessness in Los Angeles. It also serves as a reminder that homelessness does not only mean living on the streets, and can take many forms. This includes transitional housing, staying with family or friends and couch surfing.

Joaquin Renteria Jr., 37

Large palm trees and a huge red sign greet guests at the Holiday Lodge Hotel in Westlake. Pablo Herrera, the manager of the hotel, remembers clearly when Joaquin checked into the blue and gray, two-story building with white doors in mid-September. That’s because Joaquin had the inside soles of shoes taped to his feet. Herrera said he offered shoes from the hotel’s lost and found, but Joaquin refused them.

Large palm trees and a huge red sign greet guests at the Holiday Lodge Hotel in Westlake. Pablo Herrera, the manager of the hotel, remembers clearly when Joaquin checked into the blue and gray, two-story building with white doors in mid-September. That’s because Joaquin had the inside soles of shoes taped to his feet. Herrera said he offered shoes from the hotel’s lost and found, but Joaquin refused them.

“He had a severe alcohol problem, but he was always polite and well mannered,” recalled Herrera.

Joaquin was a guest at the hotel for about two weeks. Then, on Sept. 23, a housekeeper found his unmoving body in a newly renovated room. Herrera said when he entered the room, it seemed as if Joaquin had rolled off the bed and hit his head on the wooden nightstand and was “so intoxicated he couldn’t recover.”

“There were empty alcohol bottles everywhere,” said Herrera. “We pulled out about 16 bottles after he died. It’s hard enough for people who have jobs and homes. Imagine what it’s like for people who are living on the streets.”

Where people died

Joaquin was not an isolated case. Another 70 people experiencing homelessness died at a hotel or motel last year, according to the Medical Examiner-Coroner.

The places where people experiencing homelessness died include construction sites and stairwells. The highest number of deaths was recorded at hospitals or hospices, with a total of 293 people (nearly 23 percent), though this was only slightly more than the 288 people who died on a sidewalk, street or walkway. Eighty-five people were found dead in a vehicle, and 37 in an alley. The Medical Examiner-Coroner data shows that 10 people died on a bus bench.

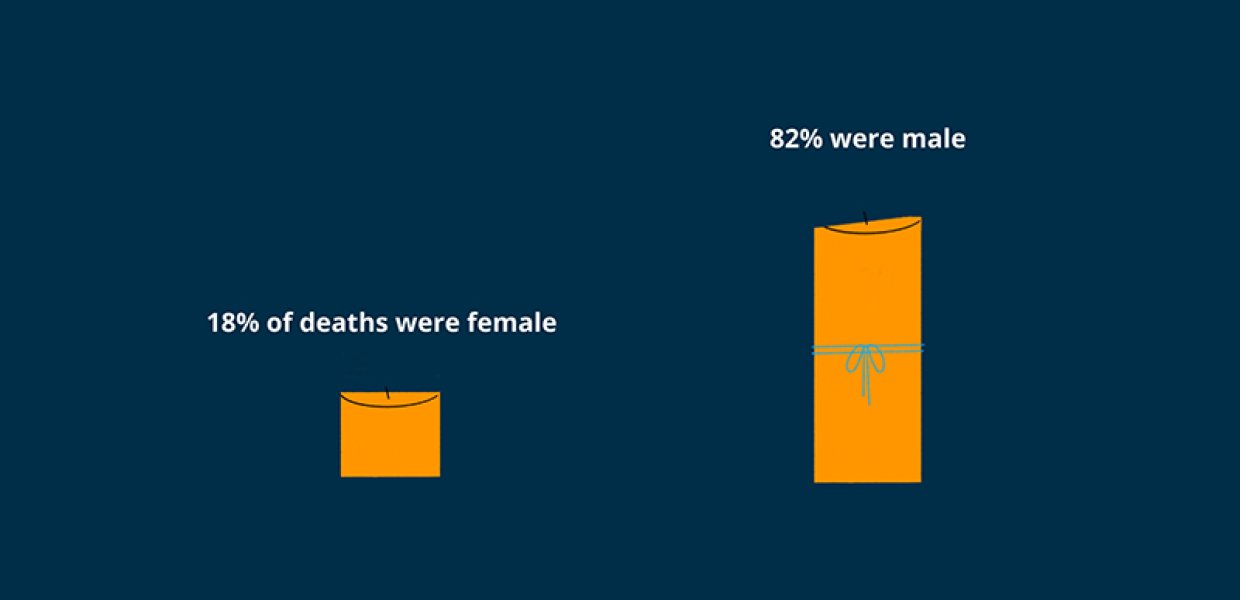

Homeless deaths skew male

The vast majority of people experiencing homelessness who died, nearly 82 percent, were men, according to the data.

“That would not be a surprise to me, given that 75 percent of homeless adults are male, and the population is aging and disproportionately Black,” said Dr. Dennis Culhane, a professor of social policy at the University of Pennsylvania who has done extensive research on homelessness.

Despite Black people making up 9 percent of Los Angeles County’s population, they accounted for nearly 26 percent of people experiencing homelessness who died during 2020. A study released in 2019 by LAHSA’s Ad Hoc Committee on Black People Experiencing Homelessness found that structural racism, discrimination and unconscious bias in housing were the driving factors in the disproportionate percentage of Black homelessness.

The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health released a report last month showing that while white people experiencing homelessness had the highest mortality rate from 2017–2019, the level is decreasing. Meanwhile, the mortality rate for Black and Latino people experiencing homelessness increased during that period.

Joshua Ray Williams, 38

Joshua was not a regular at the Jack in the Box at Sunset Boulevard and Beaudry Avenue on the edge of Downtown, where he was discovered on the ground by the front door on March 31. Frances Robles, the manager of the restaurant, said a customer called to complain about Joshua because they thought he was sleeping.

Joshua was not a regular at the Jack in the Box at Sunset Boulevard and Beaudry Avenue on the edge of Downtown, where he was discovered on the ground by the front door on March 31. Frances Robles, the manager of the restaurant, said a customer called to complain about Joshua because they thought he was sleeping.

“When I went to wake him up he looked blue,” said Robles. “I came back inside, called 911 and the paramedics came pretty fast.”

The paramedics told Robles that Joshua had overdosed and died. Robles said she was stunned.

“It’s normal for homeless people to overdose outside, so we didn’t think he would pass away or anything,” she said.

Ardalani, the spokesperson for the Medical Examiner-Coroner, said their office exhausted all resources trying to find Williams’ next of kin, but none were located.

A crisis of overdoses

Drug overdoses have been the leading cause of death among people experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County since 2017, according to the Department of Public Health. The department’s January report found that people experiencing homelessness were 36 times more likely to die of a drug overdose than the general population. Data from the Medical Examiner-Coroner found an overwhelming number of people succumbed to overdoses of drugs, including fentanyl, methamphetamines, heroin and cocaine.

According to Medical Examiner-Coroner data, 508 people experiencing homelessness last year died from complications related to a drug overdose. That accounts for 72 percent of the 704 deaths that the office classified as accidental. (Another 73 deaths were declared a homicide).

Justin Mudgett, a sergeant with the Los Angeles Police Department Valley Bureau Homicide Unit, said fentanyl overdose is “a big issue.”

“It’s been astounding,” said Mudgett. “People who are recreational drug users are dying from fentanyl, which is an instant killer for some people.”

Mudgett said each case is different, but going after their dealers is difficult because toxicology reports take six to eight weeks. He added that if officers do not find a phone at the scene with contact information, or have other evidence about a supplier, the case is usually closed without an arrest.

The link between healthcare and homelessness

According to the National Health Care for the Homeless Council, there is a high correlation between health and homelessness. That is reflected in the 315 people experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County who, according to the coroner, died of underlying health issues.

Edward Draper, 65

That includes Edward, whose health history included a brain tumor and an enlarged prostate. Jackqullen Moore, a human management information specialist at the Pathways to Home Emergency Shelter, remembers Edward as a “sweet and pleasant man.”

That includes Edward, whose health history included a brain tumor and an enlarged prostate. Jackqullen Moore, a human management information specialist at the Pathways to Home Emergency Shelter, remembers Edward as a “sweet and pleasant man.”

Moore said the shelter sought to provide all the services needed to help Edward, a Black senior citizen who had been chronically homeless, but that getting him proper healthcare was complicated by missing paperwork.

“He was looking for a place because he was tired of being on the street,” said Moore. “To me, it was like he came here to die. Whatever he had in his past, it was overwhelming and he was sickly.”

On Jan. 23, Edward died at the Pathways to Home Emergency Shelter in Historic South-Central. The cause of death was listed as heart disease. He was 65.

Edward’s story could be an indicator of a difficult future.

A 2019 report from the University of Pennsylvania found that the population of people experiencing homelessness who are elderly is expected to nearly triple over the next decade, leading to a surge of healthcare and shelter needs. LAHSA’s 2020 homeless count found that people 62 and older experiencing homelessness rose by 20 percent.

The National Health Care for the Homeless Council described the loss of employment due to poor health as a vicious cycle, given how a drop in income can quickly lead to a housing problem.

Franklin Oliveira, 63

Early on Aug. 31, Franklin sent a text message to his girlfriend. The message stated that he wanted to kill himself, and included a photo of how he planned to do it, according to Mudgett of the LAPD. Mudgett said there was not much immediate help she could provide, as they were in a long-distance relationship.

Early on Aug. 31, Franklin sent a text message to his girlfriend. The message stated that he wanted to kill himself, and included a photo of how he planned to do it, according to Mudgett of the LAPD. Mudgett said there was not much immediate help she could provide, as they were in a long-distance relationship.

That evening, Franklin made his way to the sprawling green lawns of Pierce Brothers Memorial Park, a cemetery in North Hollywood where he died by suicide.

Mudgett said Franklin’s body was found at his mother’s grave.

A mental health crisis

Franklin was far from an isolated case. The Medical Examiner-Coroner reported that 43 people experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County died by suicide last year.

According to the Harvard Public Health Review, suicide rates among homeless populations are estimated to be nine times higher than in the general United States population. At the same time, strategies focused on preventing suicide among people experiencing homelessness are largely overlooked, according to researchers.

LAHSA’s 2019 homeless count reported that 29% of people experiencing homelessness suffered from a mental illness or substance abuse disorder. Many people active in the homeless services field have long suggested that the figure is far higher. A Los Angeles Times analysis from October 2019 found that mental illness, including post-traumatic stress disorder, affected 51 percent of people living on the streets.

The Brain and Behavior Research Foundation reported that homelessness can be a “traumatic event that influences symptoms of mental illness” and can lead to “higher levels of psychiatric distress.”

Looking forward

The Department of Public Health is working on multiple fronts to reduce drug-related deaths among people experiencing homelessness. The efforts include expanding harm-reduction services, such as syringe exchange programs, increasing access to supportive housing and launching the Methamphetamine Task Force.

Another tool is the Skid Row Sobering Center. Opened in 2016, it aims both to treat people who suffer from chronic, excessive alcohol or drug use and to reduce the load on hospitals, where patients would otherwise be taken.

Yet the challenges remain for elected officials, including County Supervisor Hilda Solis, co-author of a 2019 motion addressing rising homeless mortality.

“Our number one duty as elected officials is to protect the health and well-being of the residents we serve, irrespective of their income and housing status,” she said when the Department of Public Health report was released.

The 1,383 people who died last year while experiencing homelessness show that much more work needs to be done. It will be challenging, given the scarce dollars and rising number of people falling into homelessness.

Dr. Barbara Ferrer, the county’s director of public health, said last month that the increase in homeless deaths is alarming and “requires immediate attention.”

“As we work hard to secure housing for those experiencing homelessness, we have a civic and moral obligation to prevent unnecessary suffering and death,” Ferrer said in a prepared statement. County workers, she added, “are committed to doing everything we can to reduce drug-related deaths among people experiencing homelessness and all residents of our County.”

Despite pledges to make things better, the situation may actually be getting worse. In January, according to Ardalani, 165 people experiencing homelessness died in Los Angeles County. That is a 75.5% increase over the 94 deaths in the same month last year.

How we did it: We examined data from the Los Angeles County Medical Examiner-Coroner and the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Investigators at the Medical Examiner-Coroner’s office categorize a decedent as homeless depending on where their body was found or if they do not have an established residence. Data from the Medical Examiner-Coroner includes only deaths under their jurisdiction. Some figures may change once a final year-end report is completed. Specific information on certain categories was only available through Dec. 16.

Interested in our data or have additional questions? Email us at askus@xtown.la.