Researchers from the Annenberg Innovation Lab spoke on a panel at the 2014 Digital Hollywood fall conference on Oct. 21 to discuss “re-imagining the entertainment Industry” through assessing the “spreadability” of content, looking at how fans engage with content and utilizing new platforms for storytelling. The Digital Hollywood conference, held at the Ritz Carlton Hotel in Marina del Rey, brings together entertainment and technology professionals and top executives to discuss industry developments and trends. Annenberg Innovation Lab director Jonathan Taplin, Professor Henry Jenkins, lab creative director and research fellow Erin Reilly, and lab technical director and research fellow Geoffrey Long presented research from the Lab’s Edison Project, created to observe trends and disruptions in the media and entertainment business, to a room full of industry professionals and hopefuls.

The panelists’ view — as Taplin put it — is that “this should be the greatest time in the history of the media and entertainment business.” Taplin pointed out that in the past, there has always been a “gatekeeper” between the content creators and the customers, but with companies moving forward with their own content distribution applications — most recently HBO, ESPN and CBS — they can now “talk directly to their customers.” “We’re shifting from a world of distribution to one where circulation plays an ever more active role,” Jenkins said, adding that circulation is determined in large part by the fans and their ever-increasing engagement with media content. A big part of the Edison Project’s research is figuring out how the entertainment companies can leverage this engagement to foster what Jenkins calls “spreadability.”

“Spreadability is that capacity of content to be taken from one place to the other, to be inserted in conversations and for those conversations to begin to accrue value and meaning,” Jenkins said. He uses “spreadability” in place of the widely-used term “viral.” Describing content as viral “implies a model of infection” and likens it to a virus that one infected person passes on to all their friends, Jenkins said. “That’s not a really helpful way of thinking about all the decisions we make on a daily basis of all the media that passes through our inbox,” Jenkins said, adding that the choices people make in terms of attaching themselves to content and sharing content matter. He cited Susan Boyle’s 2009 rise to fame as an example. She gained notoriety while on “Britain’s Got Talent” — a show that was “not designed for the U.S market.” But, videos of her performances were pirated, uploaded to YouTube and shared across the internet. Her popularity resulted in her album becoming Amazon’s best-selling album for that year. Another example is the popularity of Korean pop music in the U.S., brought on by Psy’s “Gangnam Style” in 2012. Jenkins said that this reflects a trend toward “young people seeking diversity,” but also the growth in “grass roots” circulation — which relies on bottom-up, individual decisions about spreading content.

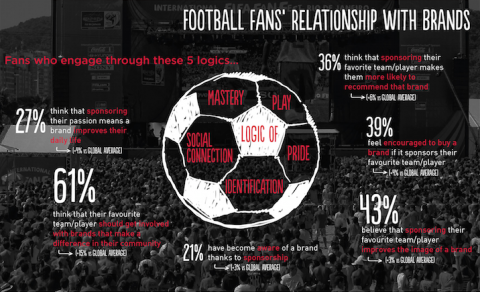

“Grassroots circulation was anticipated to be much smaller scale, more niched, more dispersed than broadcast circulation,” Jenkins said. “Instead, we’re starting to see numbers that suggest quite the opposite.” He added that people should anticipate a media environment driven primarily by circulation because the public, the fans, now decides what content gets local and national attention, as well as economic value. As such, the lab has also examined fan behavior. Most recently, they looked at engagement by sports fans — specifically soccer fans during the World Cup. Through interviewing fans, gathering big data from social media and conducting a global survey, they were able to begin reframing fan engagement. According to Reilly, people can no longer be segmented into marketing demographics, such as age or gender, so rather than looking at individual behavior, they looked at the behavior of fan communities. This led them to what they call the Eight Logics of Engagement: social connection, entertainment, advocacy, pride, play, mastery, immersion, and identification.

For example, Reilly brought up “Gangnam Style” again as an example of “play” because kids learned the dance that went along with the popular song. Reilly said that these behaviors are connected to what motivates people to spread media so that other fans can also engage.

For example, Reilly brought up “Gangnam Style” again as an example of “play” because kids learned the dance that went along with the popular song. Reilly said that these behaviors are connected to what motivates people to spread media so that other fans can also engage.

In addition to observing engagement, they are also looking into new ways to measure it and use it. Though the mainstream audience likes to be entertained and appears to be a big influencer, in many cases some of the “most important [fan] communities are really niche” and also have a lot of potential for media spreadability. The key, Reilly said, is to determine how to “leverage engagement with a more nuanced approach,” keeping masterful fans immersed, but also bringing in the more “casual connectors” — the mainstream audience. Taplin used HBO’s “Game of Thrones” as an example of varying logics of fan engagement. There are some fans who are deeply immersed and want to know everything about the show, while others engage more casually, using a basic knowledge of the show for social connection with others.

Long described the changing model of fan engagement as a shift “from attention to intention.” His research has looked at how this change, as well as the evolution of new platforms – such as Oculus Rift, virtual reality, connected homes and cities – will affect the future of storytelling. He says that a big part of addressing audience changes is determining how to best cater to different users and audiences and how to create opportunity for all of them. “When we start to figure out how to create a sustainable ecosystem for both big companies, as well as small storytellers, we’ll use these kinds of new screens, new business models, new opportunities for collaborative authorship and all of us work together to build these things,” said Long. “I think that’s where the next massive generation of the entertainment industry is going to be.”