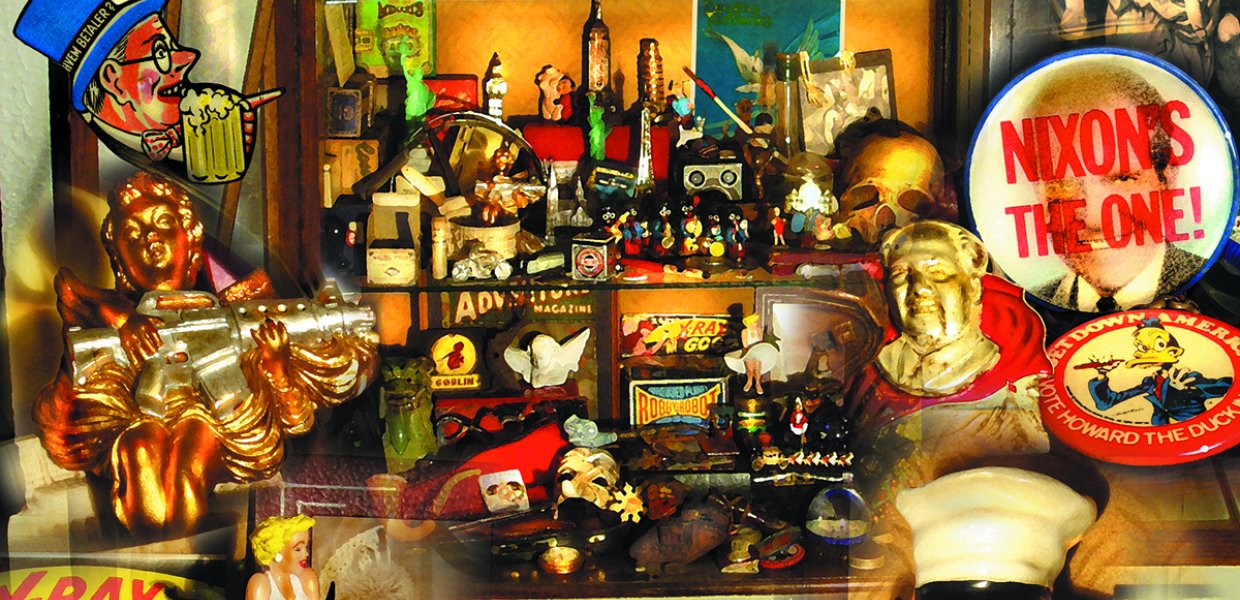

Henry Jenkins has been a collector since childhood — everything from comics, to horror posters to books and papers. “We’re all surrounded by things that we’ve chosen to hold on to,” he said. “We curate our surroundings and to some degree we construct our memory around objects that weren’t made with us in mind and yet they become part of us,” he said.

A leading researcher of popular culture and fan communities, the Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, and Cinematic Arts has now turned his scholarly eye to the collections lining his own walls. For his new book, Comics and Stuff, published by NYU Press (his first solo-authored book in a decade), Jenkins wanted to explore the idea of “stuff” and what it means to those who collect it.

Over the course of the book, Jenkins writes about not only collecting, but also what we inherit, often from family members. “It is all of those things we do with our stuff as we try to sort who we are and what our surroundings should be,” he said. Jenkins also explores the larger question of what he means by “stuff” in relation to comics — the questions of what artists add to their comic panels to visualize the world they want to reflect.

In order to dive even further into these topics, Jenkins is holding a series of virtual book club events this month. The first one was held on June 17 and is available on YouTube. The second event will be on Tuesday, June 23, and the final meeting is on Tuesday, June 30. We asked Jenkins to give us a little background into the book and why he wrote it.

I’d never written about collecting before because it was kind of this thing I was holding at the greatest distance. Fans have been seen as hyper-consumers and their collections were often held up for ridicule, those were the signs of their extreme fandom — adult men collecting toys, a Saturday Night Live sketch about Star Trek fans who just want to buy autographs or programs — or are just obsessed with getting stuff. And so, that was the site of shame for me in writing about fandom. And I didn’t want to write about it until I had an explanation that I felt comfortable with. I found this literature in anthropology that talks about mapping meaning onto our objects; this gave me a way to talk about this subject that wasn’t just about buying things but mapping the meaning to those objects and how that turns buying things into something we call our belongings.

In addition to material “belongings,” you discuss comics in your book. What has changed about comics over the years?

The shifts have been in a few ways. In the last three decades there’s been a move for more and more artists to write about everyday life and to draw pictures of everyday life — to take seriously the novel part of the graphic novel. They are also moving from big heroes battling it out to still lifes — and this change has resulted in greater prestige. For me, there’s something very interesting in that shift. Drawing the details in the comic is something the comic artist chooses to do at their own cost. You could do a panel that has no stuff in the background, and it would be acceptable to the publisher, but the artist is choosing to meticulously draw these things in, to track down references and make sure they have all the details right.

The artist is obsessed with these details, and that obsession is part of what interested me. Why are those details meaningful to these artists? And then, as the artist begins to look at and track down these details, they start to reflect on their own collecting practices, their own relation to the material world. They’re something we see and notice, and yet they’re also part of the background.

What kind of readers will be interested in this book?

I wrote this book for myself more than almost anything I’ve ever written, and it’s a beautiful book with a hundred color pictures that speak to my favorite comics. So that’s number one. It’s a very interdisciplinary book that combines art history, literary studies, anthropology, media studies, comics studies, fandom studies — so I hope it appeals to people who could never figure out what they wanted to major in during college. I also want it to be as much a book for people who care about stuff, as for people who care about comics. You can come to the book from either vantage point and hopefully walk away with a deeper understanding of what fascinates you. And probably with a large list of books you want to buy and read.