Students in University Professor Geoffrey Cowan’s class follow history in real time. The conversation might center on breaking news about wildfires in California, debates over arts funding in Los Angeles or the latest international conflict. Students quickly see how the press shapes those stories and their own lives.

For some, the first assignment — writing both an autobiography and a biography of a classmate — sparks unexpected friendships. For others, conversations with guest speakers have even led to job offers. What unites them all is the feeling that they’re part of something bigger: a living, ongoing dialogue about democracy and the press.

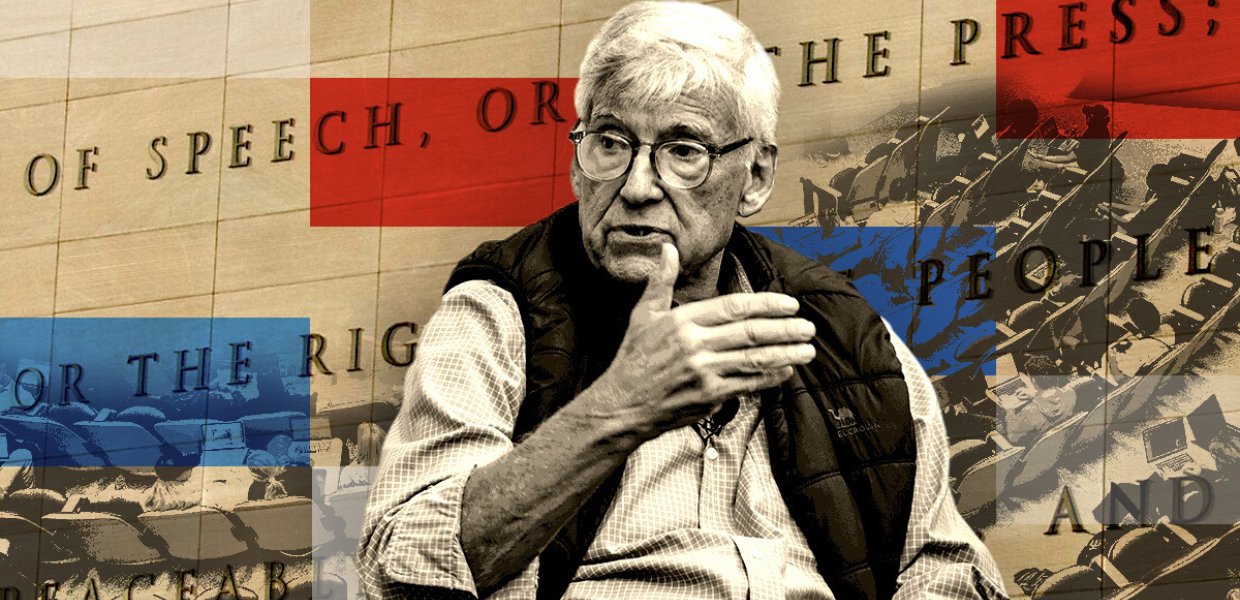

Cowan has taught JOUR 200: The Power and Responsibility of the Press for nearly a decade, guiding close to 2,000 USC students from majors across the university. Many don’t plan to become journalists, but they come because the class offers a chance to engage with pressing issues, to hear directly from Pulitzer Prize-winning reporters, community leaders and even fellow students.

The class dives into journalism’s impact from every angle: history, law, politics, technology, ethics, and pop culture. Students are expected to ask tough questions, engage in discussion, and connect what they’re learning to breaking news as it unfolds. “My goal is to help students see both the continuity and the change, and to feel that they are part of this larger conversation about democracy and the press,” Cowan said.

That mission feels especially relevant now, as the world marks the International Day of Democracy on September 15. “You can’t have a democracy without a free press,” Cowan said. “The tools keep changing, but the core values remain the same. What I want students to see is that they’re part of this larger conversation — and that their voices matter in sustaining it.”

In your class, you start with the big question: What is journalism, and why does it matter? As we celebrate International Day of Democracy, how do you explain the press’s role in keeping democracy healthy?

I tell my students that journalism is about educating people on issues that matter — whether at the local, international or even personal level. At the heart of it is truth. In my first class, I ask: Does truth matter in science, in business, in film? Of course it does. And it matters just as much in journalism.

To bring this alive, I invite a wide range of voices into the classroom — from former White House Counsel John Dean, who speaks about being misrepresented, to writers, producers, and Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporters. Students see that journalism isn’t about being “the enemy of the state.” It’s about holding institutions accountable — sometimes even USC itself — not out of hostility, but because truth makes us stronger. That’s the role the press plays in keeping democracy healthy.

The First Amendment says the press should “serve the governed, not the governors.” In today’s divided political climate, do you think the press is doing that well — or are there areas where it’s falling short?

What I worry about most is the decline of local news. Local journalism plays two crucial roles: accountability and cohesion. Accountability journalism keeps governments and corporations honest; studies even show communities without a strong local press face more corruption and higher bond ratings. Cohesion journalism, on the other hand, connects people to one another. It tells you who your neighbors are, what happened at the basketball game, or who just got married. Both are vital, and both are at risk when local journalism fades.

Without that foundation, our national conversations become more polarized and less grounded in shared facts and experiences. Strengthening local journalism isn’t just about covering city hall or school sports. It’s about upholding the democratic fabric of the country.

Around the world, we see journalists facing censorship, harassment, even violence. What do those risks tell us about the state of democracy globally, and what should your students here at USC take away from that?

Sadly, threats to journalists aren’t new — they’ve always existed, and in some places they’re worse than ever. That’s why efforts like Voice of America mattered so much, bringing reliable information into places where it was otherwise suppressed.

I try to help students see this in a personal way. In one class, I asked how many came from immigrant families, and nearly 40% raised their hands. Their experiences remind us that the free press isn’t just an American issue. It’s a global one, with very real consequences in their home countries.

Part of my goal is to make students feel they’re part of a larger, ongoing conversation — not a partisan one, but a global one. That’s why I bring guests into the classroom, encourage dialogue and give students chances to connect. This reminds students that democracy depends on a press that can do its work without fear, and that their voices matter in sustaining it.

With so many people getting news from social media, influencers, or even AI, how do you see the idea of a “free press” evolving? Can these new platforms play the same role in supporting democracy?

There are certain enduring values in journalism that don’t change: It has to be accurate, verified, independent and courageous. You can’t have a healthy democracy without that. What does constantly change, however, is technology. At the time of the First Amendment, the ‘press’ meant pamphlets printed one sheet at a time, often partisan and vicious. Later it was radio, then television, then cable and streaming. Today it’s the internet, social media even AI. Each wave raises new challenges, but also new opportunities to inform the public.

In class, I try to show students how these shifts play out. Norman Lear once spoke to them about the first time he heard radio in the 1920s on a “crystal set,” a revolutionary technology at the time because it was the first reliable and affordable radio receiver made available to the public. More recently, we’ve talked about TikTok, disinformation and even what it means to moderate content online. And sometimes we use very local examples like the Los Angeles Times story about a fight over the value of palm versus shade trees at LACMA to show how the press, old or new, can influence public debate.

I remind students that you don’t have to be a professional reporter to practice journalism. In Syria, when no outside media could show what was happening, citizens created their own news outlet. That spirit — seeking truth and making it public — is what matters most. Platforms will keep changing, but the essential role of a free press in supporting democracy remains the same.