The year was 1995. In a Blockbuster Video parking lot in Virginia, Myoung-Sun (Kelly) Song sat in the family car, waiting for her mom to return some rented movies when “Gangsta’s Paradise” by Coolio came on the radio. Song, who was born in Seoul and lived in the U.S. for three years during elementary school, was transfixed by what she heard.

“I was still learning English at the time and was quite young,” she said, “so I couldn’t understand the lyrics. But the beat was enough to catch me because it was unlike any other song I’d heard before. From this moment, I became an avid hip hop fan.”

Twenty years later, as a doctoral candidate at USC Annenberg, Song’s dissertation focused on Korean hip hop. She received her PhD in Communication in May of 2016 and the previous fall, organized a Visions & Voices event at USC that was an extension of her dissertation and which brought some of Korea’s most influential hip hop artists to Los Angeles.

The interviews Song conducted for her dissertation have now been turned into two books, volumes 1 and 2 of Hiphop-Hada, which were published in July by Annapurna Book. The title means, roughly, “to do hip hop.” Song explains, “By adding the Korean verb ‘hada,’ which means ‘to do,’ with a noun, it becomes a verb of its own. So adding hip top to ‘hada,’ Koreans frequently use hip hop as a verb: to hip hop.”

The title, she said, “represents how hip hop is created, lived, and shared by artists in Korea. It also reflects the very nature of Korean hip hop as it continues to change and evolve to reflect the society and culture that it is a part of.”

Many Americans might not know anything about Korea’s hip hop history. Song said that hip hop first started to take root there in the early nineties, just a few years before she heard “Gangsta’s Paradise” on the radio.

“It’s safe to say that the Korean public got their first glimpse of hip hop through the sensational 1992 debut of the group Seo Taiji and the Boys, who broke out into the music scene with a dance song infused with rap segments,” she said.

With the rise of the internet, hip hop made the leap from the U.S. to Korea.

“In America,” Song pointed out, “it’s not uncommon to hear people say that ‘hip hop started in the streets.’ In Korea, hip hop did not start in the streets. It started in the bedrooms and homes of Korean fans of American hip hop, who logged onto their personal computers and joined community bulletin boards.”

Like modern fans of any type of pop culture, Korean hip hop fans connected with each other first online, sharing lyrics and news, and then offline.

Tapes and CDs would be brought back from America by Koreans who had traveled abroad and then in the artsy neighborhood of Seoul called Hongdae, hip hop fans would meet for “listening sessions.”

“Because hip hop cassette tapes and CDs were rare at the time, it was not uncommon to have 100-200 people join,” Song said. They crowded into cafes and clubs to listen together.

From there, fans became creators.

“Those with a creative drive began to think about what Korean hip hop would sound like. They started writing lyrics, making beats, and performing together. From these activities, Korean hip hop as cultural and musical entity began to grow.”

When Song began work on her dissertation, “Hanguk, Hip Hop: The making of Hip Hop in South Korea,” she quickly realized that the sources she needed didn’t exist. And so she went to work creating her own.

Song put her own stamp on the interviews she conducted with over 40 Korean hip hop artists. Instead of a basic question and answer format, Song devised a more flexible, creative way to work with her subjects.

“I brought along a spiral bound sketchbook and a set of 12 colored markers. I asked each artist to freely draw his or her life using these materials,” she said. The aim was to create a log of “important moments in each artist’s life including the first time she or he heard hip-hop, wrote lyrics, recorded music, performed on a stage, released an album.”

The results were as varied as the artists. Some took minutes, some took an hour. Some used different colors to “code” different periods in their life. Some added doodles, arrows, illustrations.

After the timeline was finished, Song talked to them.

“Using these drawings as sign posts, I asked each artist to narrate his or her life for me. This part of the interview took anywhere between thirty minutes to three hours. As oral history, the life timeline interviews not only capture how hip hop traveled, took root, and grew in Korean society and culture, but also allows the autobiographical to be contextualized within larger conversations of local/global, national/transnational, personal/public.”

Song said she was grateful for the support of Annenberg, as well as the USC Graduate School and the USC Korean Studies Institute, as she did her fieldwork in Korea.

Song’s dissertation didn’t just stay on paper. It inspired a USC Visions & Voices event in November of 2015 that brought some of Korea’s most influential hip hop artists to Bovard Auditorium.

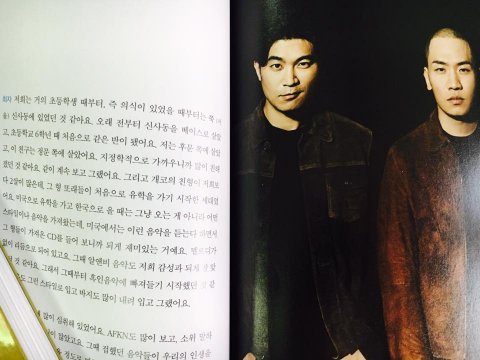

Before the concert, Song conversed with “Garion, a hip hop duo recognized as the godfathers of underground Korean hip hop; Dok2 and The Quiett, co-CEOs of Illionaire Records and two of the most successful rappers in Korea today; and DJ Son, Korea’s first internationally award-winning battle DJ and turntablist.”

Working with Professor Josh Kun, as well as the Visions & Voices team and other offices around campus, Song brought to life a night of conversation and music that was open to USC students, faculty, and staff, as well as community members.

While Song found logistics to be the most challenging aspect of the event (particularly arranging for performance visas for the international guests), the results were worth the work.

“The most rewarding aspect about our event was that it was the first time that we were able to introduce Korean hip hop in an academic setting not only to our USC community but to Los Angeles,” she said. “We had a full crowd at Bovard and it was amazing to see how music truly transcends linguistic, cultural, historical, and geographical boundaries.”

Currently, Song is teaching in Korea, at Sogang University’s American Culture Studies department. She’s also conducting follow-up interviews in the hopes of turning her dissertation into a book. As of this fall, Song appears weekly on a Korean radio show that focuses on K-Pop, where she brings the stories of the Korean hip hop artists featured in Hiphop-Hada to a wider audience.

Song is proof that a doctoral dissertation can be flexible, creative, and can lead to other endeavors, like her Visions & Voices event and the Hiphop-Hada interview collections.

“I feel very lucky that parts of my dissertation were malleable enough to be turned into something that could be enjoyed and shared with the wider public,” Song said.

The key? “I think the most important thing to keep in mind is to research something you are truly passionate about,” she said. There will be ups and downs as you work on your dissertation, so having that foundation is important.

“Don’t be afraid to take breaks, to share stories with your peers, and most importantly, to try something different!”