Like a game of telephone on steroids, rumors and hoaxes on Twitter travel as fast as a user can tap the little “retweet” arrows.

Sometimes online rumors are silly and ultimately inconsequential, like the recent hoax that had a former 90210 actress engaged to much-older comedian Jon Lovitz. But other times, rumors can have a real, tangible effect, such as those about vaccines causing autism or those that target political candidates.

During the 2012 U.S. presidential election campaign, Professors Lian Jian and Francois Bar, along with Annenberg doctoral students Jieun Shin (ABD) and Kevin Driscoll (Ph.D. 2014), trained their sights on the political rumors that were proliferating online.

Their paper, “Political rumoring on Twitter during the 2012 US presidential election: Rumor diffusion and correction,” was published in the journal New Media & Society.

Shin, Jian, Driscoll, and Bar believe that their analysis is the first of its kind. While “rumor scholarship” has a long history, political rumors have not been studied on a large scale.

The research team was first interested in the viral nature of online rumors in general.

“Our team was initially interested in investigating the rumor diffusion process on social media as opposed to the online political sphere or the political nature of the rumor,” said the paper’s first author, Jieun Shin.

“Given the rapid spread of rumors in today’s media environment, our research team was curious to know the role social media plays in this process and how individuals transmit unsubstantiated information within a networked-media system.”

When they began work in 2013, however, they realized that a “perfect dataset” already existed: political tweets collected by the Annenberg Innovation Lab between October 2011 and December 2012, a period that included the 2012 U.S. Presidential campaign.

The team began by identifying over fifty rumors taken from three fact-checking websites.

“One of the rumors suggested that Mitt Romney’s campaign slogan was identical to the KKK’s,” said Shin, “while another asserted that Barack Obama’s birth records were sealed.”

They then aimed to discover how these rumors were transmitted on Twitter, as well as what difference (if any) fact-checking websites had on stopping the rumors.

They found that political rumors both spread quickly and were difficult to correct because of one factor: Twitter users tend to self-segregate, following and interacting with other users who have similar points of view.

“We observed that Twitter users selectively transmitted rumors about opposing candidates and formed polarized communities based on the rumors’ target,” Shin said.

Twitter users who spread anti-Obama rumors rarely also spread anti-Romney rumors, and vice versa. In that way, the researchers said, “Social media often functions as an echo-chamber that reinforces individuals’ pre-existing attitudes.”

A user spreading an anti-Obama rumor was likely to have followers who would retweet an anti-Obama rumor and unlikely to follow someone debunking it.

It was a perfect environment for these rumors to thrive, spread, and stubbornly refuse correction.

After using keyword searches to narrow down their data from 300 million tweets to a more manageable 439,556 tweets, the team worked with undergraduate coders to ensure that all of the tweets within the data set were political rumors.

The student coders weeded out keyword matches that had nothing to do with the rumors. They then distinguished between tweets that supported the rumor and those that debunked it.

Their findings? Disheartening, if not entirely surprising.

In their paper, they write, “Overall, there were few tweets rejecting any rumor in our dataset, be it true or false.” Out of 33 false rumors, there was only an average rejection rate of 3.37%.

Rumor tweets were also retweeted at a much higher rate than non-rumor tweets.

While fact-correcting websites face an uphill battle, Shin and the Annenberg research team suggest one easy-to-implement change.

“We found that fact-checking sites’ headlines often stated false claims without clearly indicating the verdict. When users retweet such headlines, their act of sharing a correction eventually spread a false rumor,” said Shin.

Unless you click on the link, the headline has the effect of repeating the false claim. The paper suggests that websites “clearly state their verdict within their headlines or tweets.”

Still, said Shin, “It looks like we are facing a huge challenge when it comes to deeper issues such as political polarization on Twitter or social media in general.”

Encouraging critical thinking is not enough. Said Shin, “Depending on one’s existing attitude, a preposterous rumor can sound perfectly plausible to some.”

One silver lining for the researchers? A rumor coming from a satirical website was much easier to tame. Perhaps because the evidence against a satirical rumor is so clear and abundant, said Shin, “Even those who are predisposed to believe the rumor would not spread it, perhaps because people do not want to humiliate themselves by believing in obviously false information.”

As the 2016 presidential campaign heats up, the Annenberg team hasn’t observed much of a change in online political discussion.

“Misinformation still abounds on the Internet and seems effective in strengthening partisans’ support for the candidate,” said Shin.

More of Donald Trump’s statements during the 2016 campaign have been deemed “false” by fact-checking organizations than other candidates, yet his support in the polls shows no signs of flagging.

Shin and her colleagues point to Trump’s presence in the race as a key difference in political rumor dynamics in 2016, and as something that could be a harbinger of changes to come.

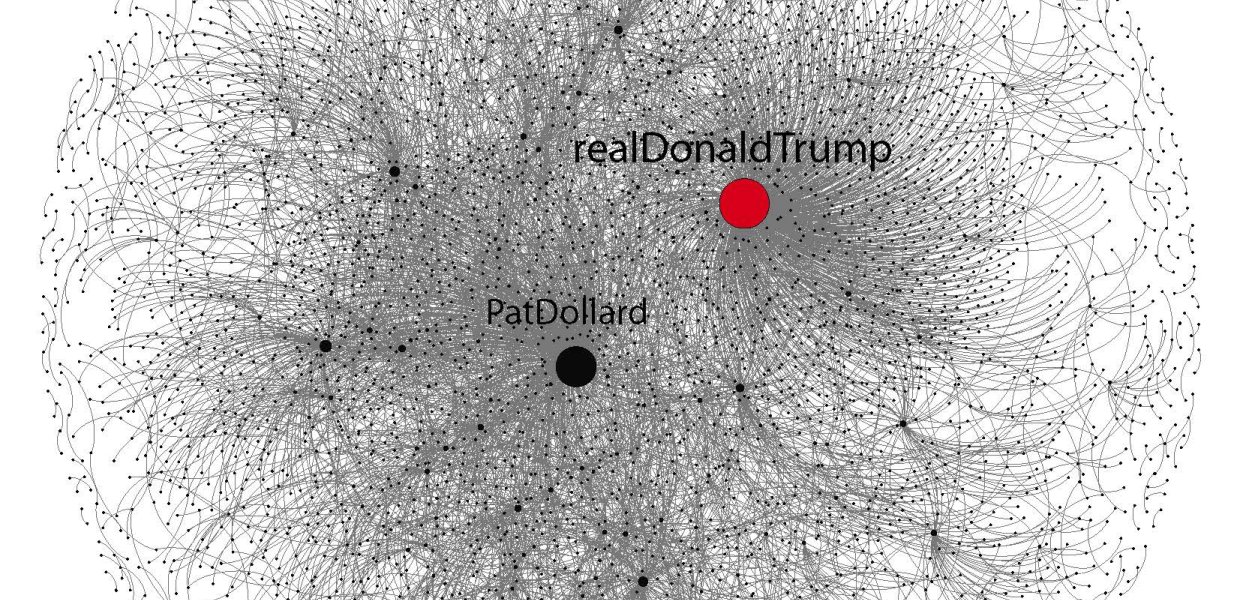

In 2012, Shin said, “Our data found that Trump was at the core of the rumor asserting that Obama’s wedding ring bears the Arabic words ‘There is no god but Allah.’” Trump’s wedding ring tweet was retweeted 718 times and Trump was found to be the most influential user in the matter of the ring rumor’s spread.

Now that Trump is tweeting as a candidate, rather than a political spectator, what effect might his success have on the future of online political rumors?

“With Trump’s success as a candidate, it would be interesting to see whether rumor/conspiracy tactics are a viable or even an attractive option for politicians to win an election. At least, this burning question will remain in the heads of our research team throughout this campaign.”