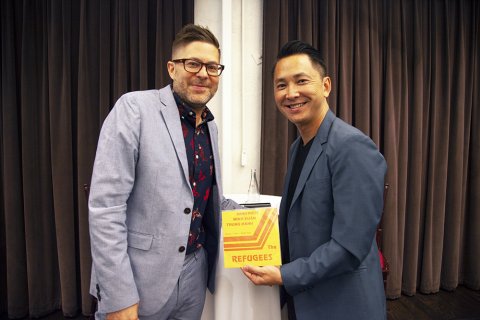

The Oct. 3 gathering at the University Club was not the first time Josh Kun and Viet Thanh Nguyen sat around a table to talk about writing, interdisciplinarity and crossing borders. After all, the pair were actually in the same dissertation writing group at UC Berkeley in the ’90s.

Fast-forward a couple of decades, and both are now MacArthur Fellows and high-profile USC faculty: Kun as director of the School of Communication, professor of communication and journalism and chair in cross-cultural communication at USC Annenberg; and Nguyen as University Professor of English, American studies and ethnicity at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

Their conversation, titled “Crossing borders, blurring borders: Writing and refugees,” was part of the Race, Arts, & Placemaking series. The talk had a familiar, intimate feel as they discussed how their willingness to cross literal and figurative borders in their work has given them the broad context and specific skills needed to critically examine the refugee crisis around the world.

The experience of immigrants and refugees is also central to the work of both professors. Nguyen’s personal journey as a refugee from Vietnam continues to drive his work. “By the time I got to Berkeley in the 1990s, my parents had just finished a long stint working in a grocery store, 12-to-14-hour days,” he said. “There’s no way I could go home and tell my parents that I'm just going to study the Romantic poets. … In order to see a career for myself as an intellectual or an academic, I needed to see that my academic work and my creative work could have an impact outside of my own life.”

Nguyen’s focus on the refugee experience has now become even more relevant, given current events. “When my short story collection on refugees came out in 2017, this was right about the time that the new administration was trying to push through this Muslim ban,” Nguyen said. “It does seem to me that it’s increasingly urgent to address refugees as a local, national and a global phenomenon.”

Having spent his career exploring the intersection of identity and power in music and culture — for both the academic and the popular press — Kun said that he has found it almost impossible to write about pop music without foregrounding questions of race, ethnicity and politics.

Known for his deep expertise in U.S.-Mexico border culture and how that manifests itself in Los Angeles, Kun recently traveled to Germany to research music and migrant communities there. “Many of the musicians I approached who came to Germany as refugees told me they did not want to be interviewed within that frame,” he said. “That wasn’t a term they identified with and one that often robs them of subjectivity and agency.”

Telling their stories in an authentic way, he said, was like “learning a new language about how to talk about freedom of movement, about displacement and dislocation about being newcomers.”

Nguyen also shared his own tale of the complicated relationship displaced people have with the “refugee” label. “I recently went to Boise, Idaho and give a talk at a public high school that had a refugee program,” he recalled. “There were literally dozens of teenagers from all over the world who were refugees. As an icebreaker, I asked them, ‘How many people in this room are refugees?’ Nobody raised their hand. How many of you are immigrants?’ Then some of them raised their hands. There's a stigma attached to being a refugee, even if there are benefits attached to it as well. It is a very ambivalent identity or category to define yourself in.”

Kun and Nguyen added that the plight of refugees — caused by the forces driving them from their home countries, and the many challenges they face in their host countries — will remain among the most pressing world issues for a long time to come. “This not just a refugee crisis created by one war,” Nguyen said. “The refugee crisis was created by a variety of different wars, a variety of different crises, including climate crises, that are not going to go away, but only going to get worse. And it's a crisis that no country can insulate itself from, even though obviously many countries would like to insulate themselves from them.”