Intellect and empathy. Anna Deavere Smith credits her grandparents with instilling these qualities in her as a young girl growing up in Baltimore, Maryland. Now, as an actor and playwright, she relies on intellect and empathy to help her master myriad roles on stage and screen from hospital administrator Gloria Akalitus on Nurse Jackie to HBO’s Notes from the Field, in which she portrays 19 real-life individuals along the school-to-prison pipeline.

In particular, she remembers the conversations she would have with her grandfather and his guiding words: “If you say a word often enough it becomes you.”

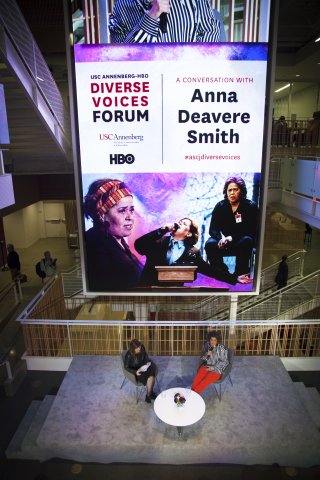

As part of the USC Annenberg-HBO Diverse Voices Forum, Deavere Smith sat down with Vice Dean and Director of the School of Communication Sarah Banet-Weiser to talk about her craft and inspiration.

Deavere Smith delved into how she uses her one-woman plays to address issues of social injustice, drawing attention to the criminal justice system, racial inequity and police violence. For example, in addition to Notes from the Field, Deavere Smith also wrote Fires in the Mirror: Crown Heights, Brooklyn and Other Identities, focusing on the 1991 race riots in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, and the award-winning Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992, contextualizing the Rodney King uprising.

“I’m not an activist. I’m an artist,” Deavere Smith said. “I have to spend a lot of time thinking about this, writing this, learning this, feeling this. Maybe with HBO and Notes from the Field I have an opportunity to reach a more diverse audience.”

In Deavere Smith’s own words, here are several highlights from the discussion.

Merging an artist with a project for social change

I ended up in an acting class by fluke. At the time, I was in San Francisco, having grown up in Baltimore and educated in Philly, I was really there because I wanted to change the world and I thought the revolution was out there. In this acting class I was taking, people were changing.

I was like, “Wow, everybody’s changing. Maybe there is some type of science to this change that I should learn that I could apply to changing the world.” And then it just happened. It got clear that this is something I could do.

I never lost that desire to try to change the world. I always thought that’s what I was doing even when I had to do little walk-on parts or whatever they were telling me to do…

Call to action

We come from a tradition of “call and response,” of shouts, field hollers and blue shouts. So, we sent this group of 500 people every single night out all over the theaters, director’s office, dressing rooms and on the lawn to talk about what they were going to do as a response.

We collected what people said, what they would do and had facilitators hold group discussions. The hardest part is, really, what question can you ask a group that’s meaningful. It could be, “What are you going to do?” and you’ll receive, “I'll tutor,” or “I'm going to write a check” or “I’m going to run for school board.”

We ended the production in Boston thinking it would be more constructive to ask people what their proximity is to these issues that we were discussing were. There’s a lot of activists now talking about proximity to the problem and I think that's the first place to start.

We need choir rehearsal. We need art to convene us to come out of our houses, out of social media. We need to be together with strangers and we need to be together with people who want to make a change.

Weight of history in contemporary interactions

I think that the knowledge of history is the opposite of hopelessness. You know some things about where you come from or if you’re interested in yourself as a person, that you are a continuum of narratives.

You’ll know things that happened in your past and some of those things could have been fantastic. Some of them could have been not fantastic, but when you understand that not fantastic thing, that’s what you need as a springboard to put yourself in the future. I think that history gives us a way of clarifying the situation so we know where to go and where not to go.